DVGW has confirmed: drinking water hygiene and energy savings aren’t necessarily a contradiction in terms – in certain conditions.

5-minute read

“Saving energy in the hot water supply – is it possible?” The German Technical and Scientific Association for Gas and Water (DVGW) addresses this question in its most recent fact sheet. The latest published document confirms in terms of content what Schell also addresses: that saving energy and water without risking drinking water hygiene is only possible if certain conditions are met. In the following, we have compiled exactly what these conditions are, always taking into account the maxim “protecting health always comes before saving energy”, as this is also required by the German Buildings Energy Act (GEG).

Should the hot water temperature be reduced?

Short-term energy-saving measures in existing buildings by means of user behaviour and flow restrictors

Short-term energy-saving measures in existing buildings with large systems

Longer-term energy-saving measures

Should the hot water temperature be reduced?

DVGW rejects a general reduction in the hot water temperature (PWH). The reasoning being: “Temperature is important for minimising the probability of Legionella multiplication ... (it) is the only corrective factor in the hot water system that reliably inhibits the multiplication of Legionella.” For this reason, hot drinking water (PWH) in large systems must be at least 55 °C at any point in the building and cold drinking water (PWC) must be no warmer than 25 °C. Dr. Peter Arens, a hygiene expert at Schell, knows for a fact that “Taking this requirement into account, there are still a few things that can be done to reduce energy costs.”

Short-term energy-saving measures in existing buildings by means of user behaviour and flow restrictors

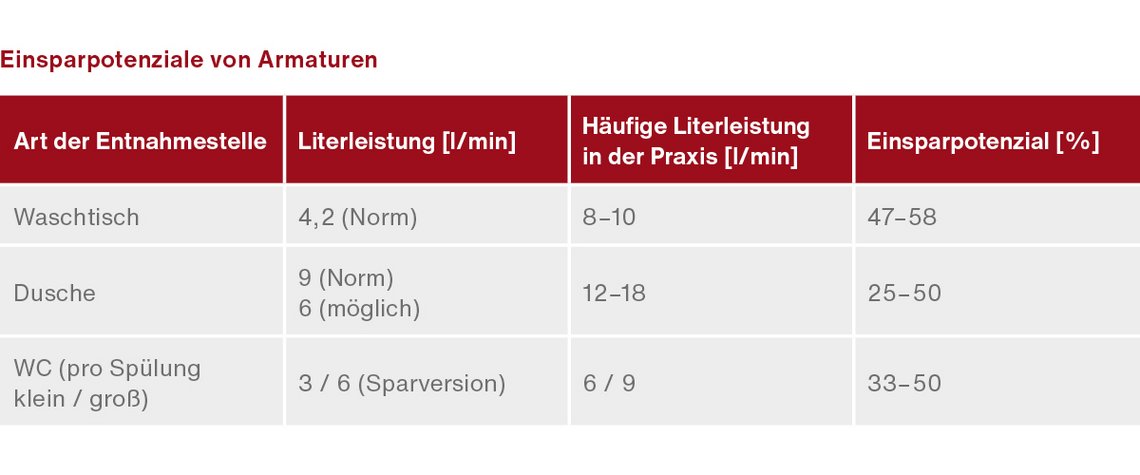

According to the DVGW, users in particular can make a big difference as a result of their behaviour. Those who use less hot water save both energy for heating and money. According to the DVGW, important parameters are the amount of water used, the set user temperature of no more than 55 °C at each tapping point and the times of use. “At tapping points with high consumption and frequent use, great savings can be achieved by means of water-saving fittings or flow restrictors,” explains Dr. Peter Arens. Dynamic flow regulators are recommended, such as the ones Schell has in its range, which limit the amount of water regardless of pressure. If a Schell angle valve is installed on a wash basin, this can be used to reduce the water volume.

- In existing systems, the drinking water installation is designed for showers with a flow rate of 9 litres/min and for wash basin taps with a flow rate of 4.2 litres/min, if the drinking water installations are planned and dimensioned according to DIN 1988-300 (2012). In practice, however, the drinking water flow rates are often higher. If the flow volume is reduced to these values, around 40% of water, waste water and hot water can usually be saved without compromising hygiene.

- In frequently visited areas such as washrooms in airports, public toilets in buildings such as offices and hospitals, etc., the wash basin flow rate can also be reduced to 3 l/min if the frequency of use is very high.

Short-term energy-saving measures in existing buildings with large systems

- What is known as the Legionella circuit (e.g. weekly or daily heating to 70 °C during the night hours) can be switched off: the reason for this is that it’s of no use in terms of drinking water hygiene in faultless hot water installations with a minimum temperature of 55 °C.

- The circulation pump can be switched off for up to eight hours at a time in hygienically safe drinking water installations. Contrary to common practice, this should be done during the day when hot water is being used anyway.

Longer-term energy-saving measures

In general, new buildings are usually much more energy efficient than older buildings with older drinking water installations. “This is because the drinking water installation can be optimally designed in the planning phase, in turn allowing investment and operating costs to be significantly reduced,” explains Dr. Peter Arens. The DVGW has this advice: in new buildings or when renovating existing buildings, the dimensioning of the drinking water heater and the pipes and fittings, etc., must be adapted to the actual consumption. In the event of renovation, this can also mean completely dismantling drinking water installations that are unnecessary.

In this respect, Dr. Peter Arens recommends planning for more T-piece installations and lower litre capacities at all tapping points in order to keep the drinking water installation as streamlined as possible. “The dimensioning of the drinking water installation should be carried out with lower flow volumes calculated instead of the values according to DIN 1988-300 Table 2. This is also explicitly permitted according to the note under this table.” This allows the potential savings in investment and operating costs to be maximised.

Summary

In its new fact sheet “Saving energy in the hot water supply – is it possible?” the DVGW includes an outline of short- and longer-term measures that can reduce hot water costs without compromising drinking water hygiene. It gives operators useful tips on how to save water and energy without jeopardising drinking water quality. Many of these tips have no cost implications. In addition, all the product solutions needed to save water are already available today from companies that, like Schell, have been active in water-scarce countries such as Spain or India for decades. The same premise still applies: protecting health always comes before saving energy.

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/b/csm_symstemloesungen_e2_thumb_6bca267f26.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/user_upload/images/menu/menu_service_downloads_broschueren.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/7/7/csm_menu_unternehmen_ueber-schell_awards_f6cec25b1d.jpg)

![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/a/0/csm_menu_unternehmen_ueber-schell_wasser-sparen_41036d2dd9.jpg)